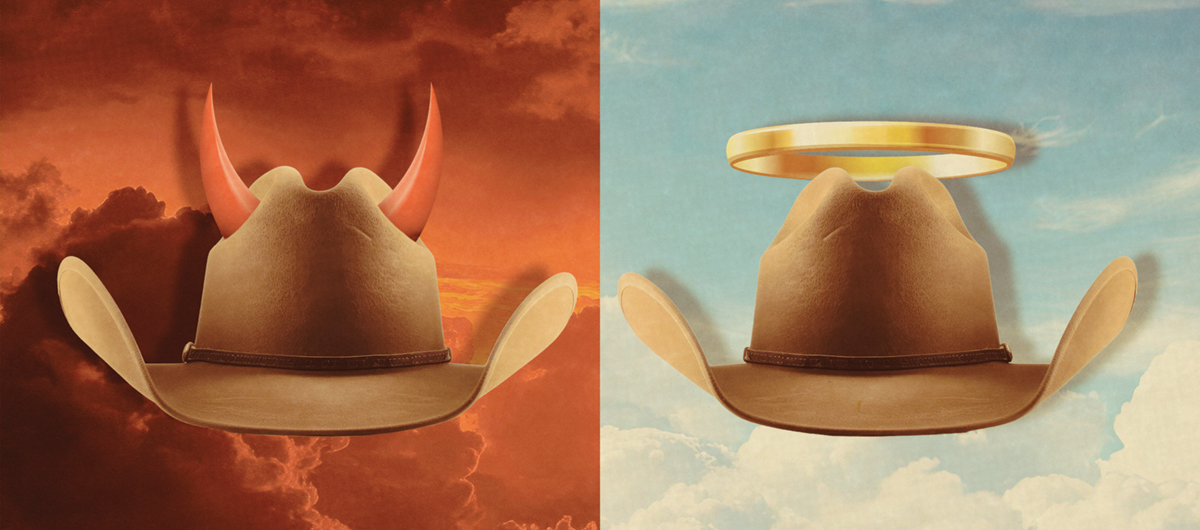

The Good Ol’ Boys and the Bad People

Since 2000, the incarceration rate for rural Americans has skyrocketed past that of their urban counterparts. Why?

Since the latter part of the 20th century, the United States has tended to rank a mong the countries with the highest incarceration rates globally. The most recent national data from 2021 counts 531 incarcerated individuals per 100,000 population, a rate that puts the US sixth in the world — lower than countries like Cuba (794 per 100,000), Rwanda (621) and Turkmenistan (576) but higher than countries such as Russia (300) and Iran (228).

That sixth-place ranking is actually an improvement from 2018, when an incarceration rate of 642 per 100,000 put the US at the very top of that global list.

But that’s not to suggest that the numbers in the US are seeing positive trends across the board. There is actually a glaring—and growing—disparity between the incarceration rates in smaller towns versus those in cities, and that disparity isn’t tilted in the direction that you might assume.

According to studies by the Vera Institute of Justice, the jail rates for urban and rural counties were roughly equal at the start of the century. Thirteen years later, the rates of incarceration were 40% higher in rural counties than in urban metro areas. Between 2013 and 2019, jail populations dropped 18 percent in urban areas but increased 26 percent in rural areas.

Those statistics are hardly the only contrasts in urban and rural incarceration. Nationally, the number of individuals who are being held in jail while awaiting trial has increased by 223% since 1970. In rural counties, however, that increase is almost double (436%), a stark rise that is disproportionately impacted by rural regions in the South and the West.

What explains these very different pictures for rural and urban incarceration rates?

Jennifer Sherman, who specializes in rural sociology, was interested in answering that question. Between 2020 and 2024, she conducted two rounds of in-depth voice interviews with individuals who had experience with incarceration in at least one of six county jails in Central and Eastern Washington. The accounts she collected were designed to augment and, ideally, help put a real-world narrative to the data gathered by her research project partner Jen Schwartz, a criminologist and fellow professor of sociology at Washington State University.

Their mixed-method research found that criminal offenses weren’t driving the higher rural jail rates as much as small misdemeanors — things like failure to appear in court or driving with a suspended license. And when the researchers looked at the context around those misdemeanors, they found that they were often part of a vicious circle that arose from challenges in navigating the law enforcement system.

Take, for instance, someone who’s had their license suspended as a result of driving while impaired. Without a license, they’re no longer legally able to drive to work or treatment services or court appearances. But in rural communities, where public transportation networks are slight or even nonexistent, personal cars might be the only option to get from point A to B. It’s not hard to see the Catch-22 that arises from this predicament, and it only leads to further ones down the road.

At the same time, Sherman heard contrasting accounts. Some individuals she spoke with enjoyed certain perks that enabled them to navigate the system more effectively. They might get a crucial insider tip or a waiver that helped them meet court-ordered criteria and avoid further jail time.

The key factor in these divergent experiences was often—but not exclusively—social class. Another kind of wealth played a role, too. Sherman calls this moral capital, which can be measured by an individual’s standing in their community. Those with more moral capital tended to experience a smoother restorative path after jail.

For a new Humanities Washington talk, which draws on her recent research on rural incarceration, Sherman looks at how jail rates might be a byproduct of rural intra-community dynamics. Titled “Bad People and Good Ol’ Boys: The Criminalization of Rural Disadvantage,” the talk considers how an individual’s social standing can affect their ability to recover after a brush with the law — or whether they will find themselves in a punitive cycle from which it’s difficult to escape.

Humanities Washington spoke with Sherman about her research and how it informs her talk. The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Humanities Washington: How did this talk originate?

Jennifer Sherman: This talk is based on research that I began in 2020 with a colleague of mine at WSU, Jen Schwartz, who is a criminologist. It began when I saw this call for proposals from the Vera Institute for Justice. They were looking for teams to study the rise in rural jail incarceration across the nation. Basically, they had this sort of uncomfortable finding, which was that rates of incarceration in rural jails had been rising for several decades nationally while they were falling in urban and suburban areas. And they wanted teams to look at what was going on. We were one of two proposals that were chosen for that grant.

And what shape did that research ultimately take?

We put this project together where we partnered with sheriff’s departments in six different rural counties in Eastern and Central Washington. And we did a combination of research. Jen was looking at booking and release data — that is, actually getting directly from them all of the data for who entered and left their jails. And then, because this was 2020 [during COVID], I was doing phone interviews with people who had spent time in the jails. There were two rounds of those interviews, which means I’ve now interviewed 71 people who have spent time in one or more of those six jails. So we’ve got these two really different datasets that speak to each other in different ways.

What were some of your findings?

We learned a ton about what is bringing people to jail in rural Washington and what’s perpetuating this problem in rural communities.

You see, when we asked the sheriff what was driving jail admission, they would tell us, “Drugs. It’s all drugs.” Well, drugs are a piece of this puzzle. But one of the most interesting findings early on was when Jen came to me and said, “A lot of what’s bringing people to jail are really small misdemeanors. They’re not really criminal offenses.”

She kind of put them all together in one category that she was calling system navigation problems. It was really little stuff like failure to appear in court, failure to pay fines or to complete court required activities, such as community service or that sort of thing. And she said, “When you put all these things together, they account for more than one-third of all the jail stays.”

She asked me, “Can you help me understand why this is driving so much jail admission?” And I was able to find in my data that the rural communities have some structural lacks that make it really hard to navigate the system once you get in it. For example, if they take your license away in a rural community, you’ve got a really tough choice now: Do you drive to work and risk getting picked up for driving with a suspended license? Or do you not go to work, which means you can’t pay your fines and fees?

So we heard a lot [from interviewees] about job loss and housing loss after an arrest and things like that, all of which contributes to people’s lives kind of spiraling out of control and them ending back up in jail. And, of course, the more times you end up in jail, the more likely you are to lose your job or your housing. It all kind of feeds on itself.

How else does the rural incarceration experience differ from, say, the urban experience?

Part of this story is also whether you receive support from your community or if you are further ostracized. Does the experience of being in a small town further help you or hurt you in that regard?

I look at a couple of different ways in which it can hurt, including exacerbating the stigma. People often felt a lot of shame around their arrests and their crimes. But when you’re in a really tight-knit community, it can be worse because everybody knows. They heard about it on the scanners. Or they saw it on the Facebook page. And word travels fast. Small towns are really good at publicizing the misdeeds of their community members in ways that cities are not.

For some people, that was a huge issue. And then for a few lucky others who had a lot of support and where the community had sort of already decided that they’re a “good guy,” they got all sorts of support that you wouldn’t have expected — things like tips from the inside, where the court bailiffs would give them hints about how to navigate the system better. Or they would be offered opportunities, such as alcohol monitoring devices for their cars that would allow them to still get to work and still navigate some of these problems that other folks could not.

Hence the name of your talk, where we see this subjective distinction between the “bad people” and the “good guys.”

Exactly. It’s like the population’s broken down into roughly two sets of folks. There are the ones that are just kind of assumed to be bad people. In fact, I have quotes from our sheriff talking about all the bad people that they have to protect their communities from. And then there’s those kind of good ol’ boys about whom they’ll say, “They’re not bad people. They just made a mistake.” And for them, the stigma doesn’t stick because they already have this protective bubble—that supportive community—around them.

And does socioeconomic status come into play here, whereby the good ol’ boys tend to be more affluent and the bad people tend to be less affluent?

Absolutely. I would say it’s not only social class but also, of course, race. There were definitely people who felt like they had been racially targeted or that their race mattered in their interactions. Some really felt like they were targeted in certain ways for being Indigenous or for being Latinx.

But I think what was most interesting to me was that class mattered more in this sample than race. And social standing in the community or social integration mattered more than either. Most of the people who had really positive [post-incarceration] experiences were more likely to be middle class, or at least comfortable. And yet if somebody was poor but had really strong social ties to the community, or was from a family that was well regarded, they still had an easier time. People that had what I call moral capital in their communities—which is basically just being known as good citizens, hard workers, or from good, strong families—did tend to have better outcomes, even if they were from a low-income background.

Did any other interesting findings emerge from this project?

One of the really interesting wrinkles to the research project is that there were two rounds of interview data. One was in 2020–21 and the other was in 2023–24.

In between those two rounds of data collection was the Blake decision. That was the state-level decision that decriminalized the personal use amount of drugs in 2021. They’ve since been reclassified as a misdemeanor, but it really changed the way we handle use amount of drugs in Washington State.

Small towns are really good at publicizing the misdeeds of their community members in ways that cities are not.

What I discovered in the research was that, along with Blake, there was some money that went into things like rehabilitative services — things like system navigation programs that actually help folks recover. And some of our communities have really run with that money and taken advantage of the opportunity to expand the services that they make available to people who come in and out of the jails who clearly have substance abuse problems.

In the communities that have made use of those opportunities, I heard really interesting stories where people talk about these shame spirals that made it so that they couldn’t recover from their addictions. And once they were provided with the right combination of often wraparound services that would include sober housing and drug and alcohol treatment, usually intensive outpatient treatment, drug court, all these kinds of things, a lot of these folks had really different experiences where they no longer felt ashamed of themselves. They now felt like they were being reintegrated into their communities and that people were proud of them. People didn’t judge them in the same way. And that was often one of the major factors that not only let them get their lives back together, but help them stay clean and sober and move on with their lives.

Aside from the Blake ruling, did COVID impact some of the trends you were seeing?

COVID definitely changed everything. The original design for the interviews was actually to be in-person in the two jails that were closest to me. And COVID threw a wrench in that. So we pivoted at that point to phone interviews, which turned out to be a real blessing for multiple reasons.

One was that it allowed me to cast a wider net and interview people across all six counties instead of just the two that I could easily commute to. Second, and we hadn’t really anticipated this part, but jail stays can be really short. So opening it up to people who were no longer currently incarcerated meant that I got a much broader sense of who goes in and out of a jail. It meant I was also speaking with people who only spent a night there for a DUI.

And doing the two rounds really helped us to see things like the impact of COVID as well as the impact of Blake — you know, different ways in which historical events had impacted people’s lives and outcomes. And without really meaning to, it allowed us to trace the explosion of fentanyl in Washington State and see that evolve through people’s stories. It’s an interesting snapshot of a moment in time.

Even if it is a snapshot, are there some potential solutions that we can draw from your findings?

One of the more effective supports that we’ve heard about are these recovery navigator programs. There are these folks—usually people with lived experience, meaning that they’ve also been through the system themselves and often struggled with addiction in one way or another—who are just an aide that helps people navigate the post-arrest experience. A lot of what they do is just literally provide rides. They’ll get you to court if you need to go to court. They will get you to your intensive outpatient program if you need to get to that. They’ll get you to treatment. They’ll help you move around these spaces where there’s no transportation. What they do is just provide for those lacks in the system.

And, finally, do attendees come away from the talk questioning this “good vs. bad” binary?

When I have presented the talk to non-incarcerated populations, there’s a lot of chuckling. Everybody sees somebody they know in the talk, or I describe an experience that they’ve heard of. A lot of the quotes that I read in the talk are from people who are really just decent humans who made a mistake or got caught up in something that they didn’t know how to get out of easily. They have multiple types of vulnerabilities sometimes.

But a lot of what they’re saying is, “Just because I did something wrong doesn’t mean I am a bad person.” To me, that’s the important takeaway. Beyond all of the details of the rural dynamics, these are often people that are struggling with all sorts of different issues that are outside of their control.

I think we’re improving our understanding of things like addiction, but we still have a long way to go, particularly in rural communities, to understanding how and why people end up on the wrong side of the law. And it’s not actually helpful to stigmatize them.

Jennifer Sherman is currently touring the state as part of Humanities Washington’s Speakers Bureau, giving a talk called, “The Good ‘Ol Boys and the Bad People: The Criminalization of Rural Disadvantage.” Find an event here.