Lavender Country Funeral

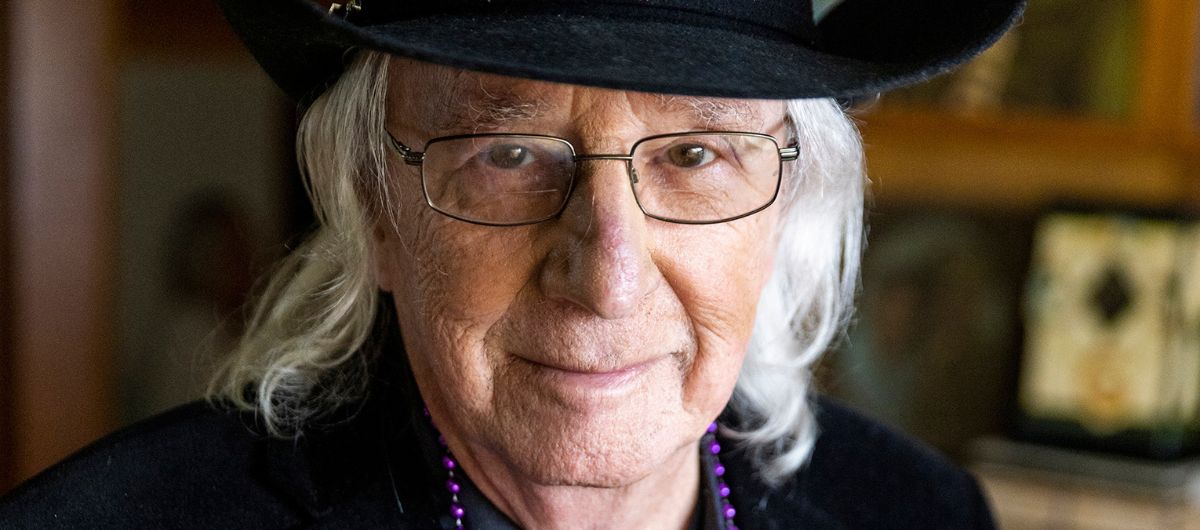

Country singer Patrick Haggerty was a stranger to me—yet attending his memorial meant everything.

I’d seen a memorial posted on social media and reached out to the organizers to ask if I may attend. I even had the nerve to ask if I could photograph. I make a living documenting living cultural traditions, meeting and interviewing artists, and documenting their work. I had just missed getting to meet, interview, and photograph Patrick, having moved to Washington mere months before he passed in 2022. I knew I wasn’t going to miss his funeral.

Patrick Haggerty is my favorite kind of icon. He was legendary to some, and unknown to most. His fame came by releasing the first openly gay country record in 1973 titled Lavender Country. The record was released, not through a major or even an independent label, but rather through Seattle’s Gay Community Social Services at a pressing of just 1,000 copies. According to Haggerty, “we sold them however we could. It was a community effort. We did some public stuff but it was really mostly a matter of word of mouth. People discovered it and turned the next person on to it.”

Those original copies circulated quietly for decades, making their way into the homes of those who wanted, what Haggerty called, “the information.” The information was knowledge, and assurance, that whatever someone was feeling about being gay, they were not alone, and they were not wrong. Years later the world would know, through a StoryCorp interview, that it was Haggerty’s hard-scrabble Port Angeles farmer father who had first put this confidence in his son, demanding he never “sneak”around. That he be open about who he was.

Lavender Country was made in Seattle, but there was a certain farm-kid empathy to its goal. Haggerty wanted to reach those who needed it most. “They could hear the music even if they lived in Pocatello,” Haggerty said, “and they could play it in their bedrooms by themselves. They could hear it, and it was like a beacon—like ‘Yoo-hoo!’”

“Patrick Haggerty is my favorite kind of icon. Legendary to some, unknown to most.”

For decades this was the fate of Lavender Country, to be a gesture from a disconnected space that reached into the bedrooms, hearts, and minds of receptive listeners, who presumably connected to its overtly gay themes, and maybe, its twangy sound. I knew this because one of those people it reached was my gay, country music-loving sister in Utah, who bought it instantly without knowing the context, and has cherished it since. At some point sharing it with me, her straight, country-music loving brother.

Haggerty would move on to other political pursuits and find a career in social work. The band would dissolve. The record would lie dormant in record bins, or as cherished items in people’s homes, but it wouldn’t circulate. Then, in 1999, over 25 years since the release of Lavender Country, it reemerged like a message in a bottle. After a mention in the Journal of Country Music about LGBTQ contributions to country music, the album was given another shot, being reissued on CD this time. But it still struggled to find an audience. Haggerty would continue to perform at senior centers around his home in Bremerton in relative obscurity.

But full recognition came when one of Haggerty’s most salacious (and maybe best) songs, “Cryin’ These Cocksucking Tears,” was uploaded to YouTube (a platform Haggerty didn’t even know about) and caught the attention of record label Paradise of Bachelors, who then gave it a wider re-release. This move courted the attention of popular music publications like Rolling Stone. Finally, Haggerty was receiving some of the attention he long deserved. Lavender Country was being invited to play festivals. They recorded a long-delayed second album (2019’s Blackberry Rose) and collaborated with artists who now operated in a more open, accepting musical world. A world Haggerty was instrumental in creating.

Trixie Mattel, the drag queen country singer who rose to fame as winner of RuPaul’s Drag Race (who wasn’t even born when Lavender Country was first released), would invite Haggerty to re-record his iconic “I Can’t Shake the Stranger Out of You” for Mattel’s first major label release, Barbara.

Patrick Haggerty died from complications of a stroke in October of 2022 at the age of 78. But his funeral wasn’t until April of 2023. Certainly some personal logistics played a role in the delay, but I can’t help think it was also for the fans —the strangers— to get the word and make plans. It was evident Haggerty had an impact beyond those he knew on a daily level. This is how I had the opportunity to attend the funeral of a man I’d never met.

At a quiet Unitarian Universalist church in Bremerton I arrived, contrite and humble, a stranger who didn’t want to disturb or disrespect friends and family. The fact that upon arrival there were buttons with Patrick’s face made me believe this was a welcome space for those of us unlucky enough to never know him, but close enough to respect we would have benefited from knowing him. I know I wasn’t the only fan in attendance.

The service, thankfully, made few concessions for us fans. The funeral wasn’t for those who had lost the legend, but those who had lost the man. His children spoke, his friends, his husband. Haggerty was an icon yes, but in that moment, he was a man. A complex man missed by legions. A poet from Whidbey Island spoke, unable to contain tears, as one shouldn’t be able at a funeral. I was glad someone cried openly. It felt right.

Directly after the service, music was made by the Lavender Country band members in the church. Later, everyone would move to a downtown Bremerton venue for a tribute concert that would go late. Both were important in their own way, but the post-service music at the church was something else.

As mentioned, “Stranger” has become perhaps the most well-known of Haggerty’s songs, owing a fair amount to the duet with Trixie Mattel. It was a song of deep longing for intimacy, of struggle and frustration about the lack of emotional depth between (presumably) gay men. Haggerty admits the song was originally titled, “I Can’t Fuck the Stranger Out of You.” It was also the song that was played in the church after Haggerty’s funeral by the members of Lavender Country, and joined by a large congregation of family, friends, and people like me—strangers.

The song is beautiful, heartbreaking, and without the more direct or biting language of some of Haggerty’s other work. Sung at his funeral, it held an ironic, bittersweet tone. Perhaps it was the number of “strangers” Haggerty had connected with through his bold DIY efforts. Perhaps it was because his husband of decades, JB, was at the center of this dancing, singing throng. Perhaps it was the relief that, after a life mostly lived in the shadows, Haggerty had finally been brought into the light for as good a final act as one could ask for.

Alan Bennett, the great British playwright, speaks of the connections forged through writing, and I think it’s just as applicable to music. In his play, The History Boys, he says, “The best moments in reading are when you come across something, a thought, a feeling, a way of looking at things, that you’d thought special. Particular to you. And here it is. Set down by someone else. A person you’ve never met. Maybe even someone long dead. And it’s as if a hand has come out and taken yours.”

Attending the funeral of a stranger is a surreal experience, more intellectual than emotional. But the deep reverence I have for Haggerty, and those who supported him in life and through pre-semi-fame, is real and tangible. Art that is made for the goal, not the paycheck, the esteem, the fame, is the only art I care about. Patrick Haggerty is a legend for his ability, his intentionality, to make people feel seen, respected, and understood. I salute this man. Y’all come out, come out, my dears, to Lavender Country.

Thomas Grant Richardson is the director of the Center for Washington Cultural Traditions, a collaboration between Humanities Washington and ArtsWA/the Washington State Arts Commission. Thomas received his PhD in folklore and ethnomusicology from Indiana University in 2019, and has worked as folklorist, writer, and consultant with numerous folk and traditional arts agencies across the county.